Written by Joss Duggan (Reading Time: 11 mins)

Razors...cutting edge wisdom? See what I did there? Putting philosophical puns to one side for a second, there's an old adage that 'there's nothing new under the sun'; that somehow, all 'new' ideas are somehow just remixed versions of wisdom that has been around for millennia. Philosophical razors are a brilliant example of this; critical thinking tools that when used correctly, just at the right moment, can be a valuable asset when sat in the boardroom or the bar.

Similar to the idea of heuristics from the world of psychology, razors work by figuratively 'cutting away' the unnecessary parts of a question and stripping it down to the essentials, so we can better understand the problem at hand.

With that in mind, here are some of the most useful razors, with some ideas for how you can apply them yourself to your life. So with that in mind, let's start with the big one...

1. Occam's Razor (Keep it simple stupid!)

By far the most famous example (and an obvious place to start), Occam's Razor is at first glance a simple truism that seems so obvious as to be unworthy of discussion. But don't be fooled! The logic and usefulness of Occam's Razor is hotly debated by the scientific community. But before getting into the nitty-gritty, here it is:

“Entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity”

Well.....for accuracy, what he actually wrote was "Plurality should not be posited without necessity", but another medieval scholar (a guy by the name of John Punch), decided that it just wasn't snappy enough and rewrote the phrase, which is now widely attributed to William of Occam. Thanks to Arthur Conan-Doyle, yet another version of this should be much more familiar to you: "When you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth".

In a nutshell, what Sherlock was telling us here, is that the simplest explanation for anything, is the most likely. So if confronted with two or more possible explanations, the one that satisfies all available evidence and has the fewest assumptions is most probably the right one.

“Things should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler!”

But there is the key - it must satisfy all available evidence. Just because an explanation is the simplest one available, doesn't make it the best one. If it fails to explain (or flat-out ignores) key facts, then it remains problematic. The best explanation then, is the one that fits the evidence, using the fewest assumptions.

2. Grice's Razor (yOU kNOW WHAT i MEANT)

Our second razor comes from philosophy of language and semantics: Paul Grice was a British philosopher who spent the majority of his career at Berkeley, developing theories on how meaning and language interact, and particularly what people mean when they 'imply' meaning.

Grice's Razor is a play on Occam's, highlighting the value of simplicity (AKA 'parsimony') in interpreting meaning. I'll spare you the long version (it's pretty dense) but the short version is:

“Senses are not to be multiplied beyond necessity”

Grice is saying that context is king and the 'literal' version of what is being said shouldn't be taken in isolation. Let's look at a quick example:

David: Kate - Are you coming to the sprint planning meeting?

Kate: Let me just grab a coffee...

After David asks the question, in the literal sense, Kate hasn't answered the question. Now I know what you're thinking: 'Don't be pedantic, we know what she meant'. But 'how' do we know?

As a reader/listener, you 'infer' meaning from the sentence; namely that Kate is going to join the meeting immediately after she has grabbed a cup of caffeine (because presumably it's going to be a long one). Even thought there isn't a definitive 'yes' or 'no' present in her response, it's safe to assume that's she'll be along soon and we when we make these assumptions every day, and when we do, we're using Grice's Razor.

Now this is why it's so frustrating when people violate this unspoken trust. When you're 'economical with the truth' and say something that whilst 'technically' true, you know it's going to mislead the listening/reader, that's a lie of omission. Honesty isn't just about using precise speech and avoiding explicit lies, it's also about being forthright with the truth when you know that someone is expecting it. To do otherwise just wouldn't be cool would it? Come on....don't be that guy.

3. Hume's Razor (Evidence must equal claims)J

“No testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle unless that testimony be of such a kind that its falsehood would be more miraculous than the fact which it endeavours to establish”

Ummmm...thanks Dave. Clear as mud.

An interesting (and incredibly annoying) feature of philosophy is that ancient writings are often easier to understand than more modern ones because someone has done the hard work of translating both the language and the meaning into plain english. With the medieval and enlightenment philosophers, whilst they 'technically' wrote in English, often they can be as impenetrable as Shakespeare to the uninitiated. So let's turn to the legendary American cosmologist and philosopher, Carl Sagan, to give us a simpler explanation:

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof”

What has now become known as 'Sagan's Standard', is a reformulation of Hume; in order to prove something incredible, the evidence must be equally incredible. For example, proving a claim such as the existence of extra-terrestrial life, would require the extraordinary levels of proof. So the literal 'awesomeness' of claims and evidence must be equal and opposite.

4. Hitchen's Razor (No evidence, no argument)

Following on from Hume and Sagan, (your extraordinary claims need some extraordinary evidence please) is Hitchen's Razor. Irrepective of your philosophical leanings, you have to marvel at the dry, acerbic and sardonic style of Christopher Hitchens. Let it never be said that Hitch ever shied away from a good debate, taking down arguments with a barrage of rhetorical techniques, whether bona fide logical device or straight-up sophistry.

First appearing in an article for Slate in 2003, and then later in his 2007 book 'God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything', Hitchen's Razor is all about the burden of proof (or lack thereof) on the recipient of an unsubstantiated claim. Here's the man himself:

“Forgotten were the elementary rules of logic, that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence and that what can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence”

It's a variation of an old latin proverb: "Quod gratis asseritur, gratis negatur" that can be accurately translated as "that which is easily asserted is easily negated". Mr. Hitchens means to say, that if you turn-up to a debate without any empirical evidence, don't expect anyone to entertain your claims and don't be surprised when you get shut-down. It's the rhetorical equivalent of bringing a knife to a gun fight and you do yourself a disservice. Though Hitchens applied this line of thinking mainly in theistic debates, it's applicable everywhere. Watch the man in action to see for yourself.

So if you've ever sat in a meeting, listening to someone talk about their pet theories (especially the HiPPo's) or observe that decisions are being made based on opinion instead of fact, this is the moment to invoke Hitchen's Razor (perhaps more diplomatically than Hitchens himself did) and swiftly bring that discussion to a close with the following phrase:

"I think that's a really interesting point you make, what data has led you to believe that?"

5. Alder's Razor (No experiment, no argument)

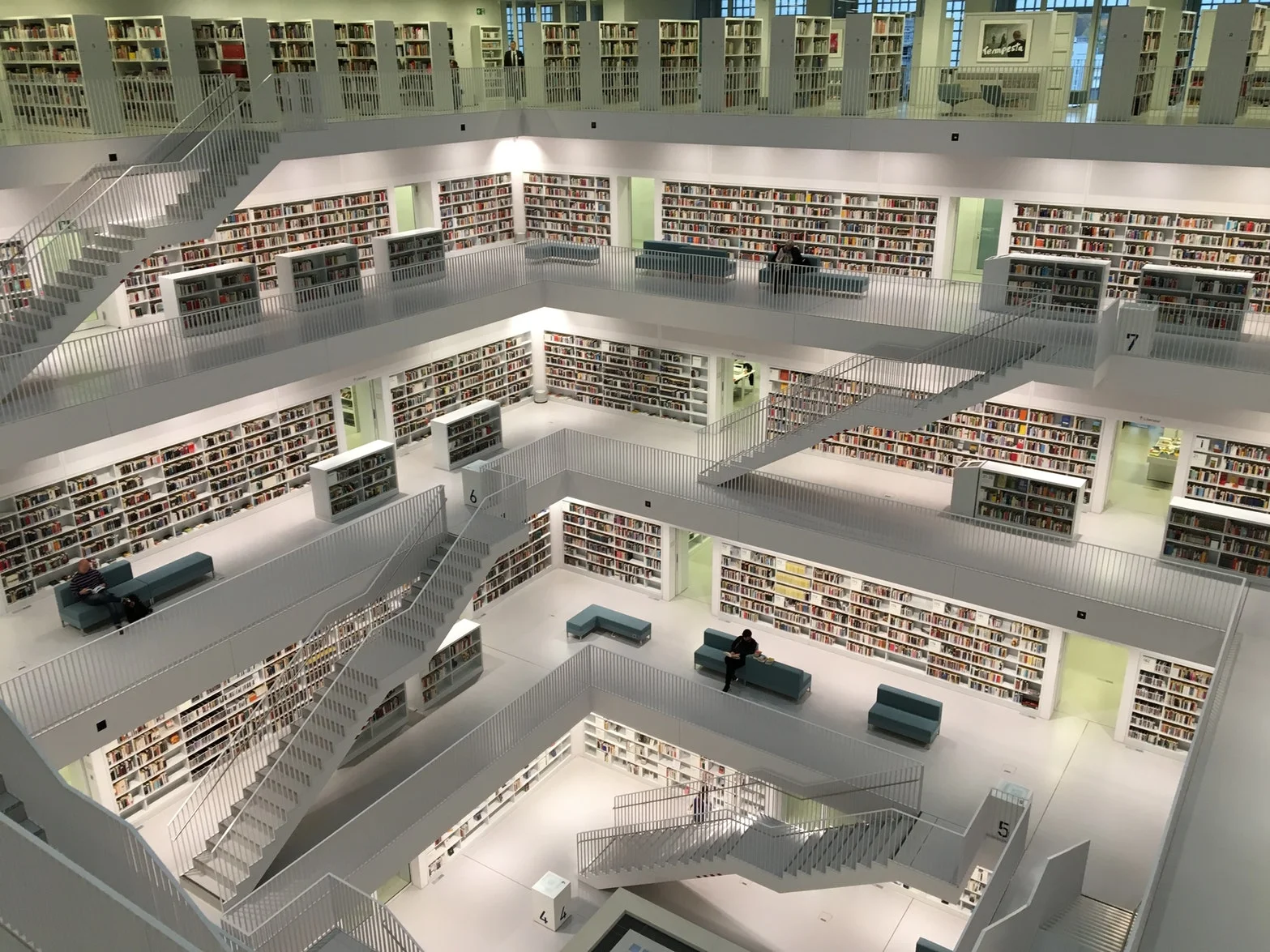

Mike Alder is an australian mathematician who in his now famous article for Philosophy Now magazine, claimed that his version is '...sharper and more dangerous than Occam's Razor'. Alder's Razor is much better known by it's altogether more colourful moniker: 'Newton's Flaming Laser Sword' (see above photo for incontrovertible existential proof of aforementioned item).

Now, I know what you're thinking....and yes. A 'Flaming Laser Sword' is really just a fancy light-saber. But less important the name and more important the concept. So what is Alder's Razor?

“That which cannot be settled by experiment is not worth debating”

It's a philosophical debate dating back thousands of years on whether or not 'pure reason' alone can solve the mysteries of the universe with intellectual giants of the field on both sides of the argument. Whatever your opinion, Alder's Razor is a useful little tool for moving forward when you get bogged down in conference room debates.

If you've read The Lean Start-Up by Eric Ries (and if you've haven't, you definitely should, it's a game-changer!) you'll understand how well the scientific method can be applied to organisations of all shapes and sizes, from start-ups to multi-national corporations and everything in between. The main idea, is to get all your assumptions out on the table and systematically work through them all to find out if your hypothesese are correct or not. This produces what Ries calls 'validated learning', which is what all young ventures should be focused on.

Now you may have spotted a problem with the application of Alder's Razor. There are many areas which it's either incredibly hard to run experiments (politics) or completely impossible (religion). Add to that, it basically kills off more than 50% of the entire philosophical canon of literature. So use with EXTREME CAUTION - let's not accidentally kill off the field completely, philosophers struggle to find jobs as it is.

6. Hanlon's Razor (People aren't evil...just stupid)

Whilst described as a computer programmer from New Jersey, something of a mystery surrounds the true identity of Robert J. Hanlon. When Alfred Bloch was compiling a book of funny philosophical musings in 1980, he received the following submission that has since become known as Hanlon's Razor. Whilst the essence of the aphorism has appeared in the writings of David Hume, William James and Richard Feynmann, Hanlon's version remains the one that's stuck:

“Never attribute to malice, that which can be adequately explained by stupidity”

When things go wrong, we seem to have a cognitive bias towards ascribing wrong-doing and 'evil' intent; when someone is late to a meeting we've called...they're disresepecting us on purpose. When the kids a few rows in front at the movies are talking, they're doing it annoy us!

In fact, this is very closely related to a well-known and substantiated cognitive bias in psychology called the actor-observer bias, wherein, whenever 'we' make a mistake, we blame temporary, external influences (e.g., the traffic made me late). Whereas when someone else makes the exact same mistake, we attribute the infraction to an internal, permanent characteristic of that person (e.g., that guy is lazy and disrespectful).

Those most susceptible to this line of thinking are those suffering from narcissistic personality disorder, as they see everyone else's actions only in reference to themselves. So if your boss, or someone you know constantly flies off the handle, blames people for their maliciousness, or even calling people 'evil'.... you may, in fact, have a narcissist on your hands.

“No-one is the villain in their own story”

Whether consciously or not, we all think of ourselves as the heroic protagonist in the sweeping, epic tales of our own lives - though we may well be the villain in someone else's.

So we must give people the benefit of the doubt; if someone has screwed up (or worse) really hurt us, it's probably not personal or intentional - they probably just didn't think it through. Everyone is doing the best with that they have - includes both IQ and EQ. So next time it feels like someone is out to get you, use the empathy that you only wish they had been able to exercise themselves.

Caveat: Never rule out the possibility of both stupidity and malice in combination, it does happen...

To Sum up

Occam - All things being equal, simple answers are better as they have less assumptions

Grice - Honesty is as much about what you don't say as what you do say

Hume - All claims need equally substantial evidence (quali or quanti) to back them up

Hitchens - If you don't have any evidence, then we don't need to have a debate

Alder - If you can't go and get evidence by running an experiment, well...refer to Mr Hitchens

Hanlon - Be patient with people (especially those without evidence) they're not (that) evil

pOPULAR articles

Further Reading

Mike Alder: 'Newton's Flaming Laser Sword' (2004)

Bloch, Arthur: 'Murphy’s Law Book Two: More Reasons Why Things Go Wrong' (1980)

Hyman Arthur & Walsh, James J.; 'Philosophy in the Middle Ages' (1973)

Carroll, Robert Todd: 'Occam's Razor' (2014)

Grice, Paul: 'Studies in the Ways of Words' (1989)

McAleer, Michael: 'Simplicity, Inference and Modeling: Keeping it Sophisticatedly Simple' (2002)

Ries, Eric: 'The Lean Start-Up' (2011)

Sober, Elliot: 'What is the Problem of Simplicity?' (2004)

Sober, Elliot: 'Occam's Razor: A User's Manual' (2015)

Stone, John R.: 'The Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations' (2005)

Thorburn, W. M., 'The Myth of Occam's Razor' (1918)